The New York Campaign (July to November 1776)

British commander-in-chief Thomas Gage had long considered New York City, where he had maintained his headquarters for nine years, as the best base from which to conduct operations to defeat the Continental Army. The overall plan was to capture New York and then move up the Hudson River Valley to meet another British force advancing from Canada, and thereby sever the troublesome New England colonies from what was widely believed in London as the more reasonable southern provinces. In the summer of 1775, William Howe succeeded Gage as commander-in-chief and inherited the New York strategy. George Washington's seizure of Dorchester Heights in March 1776, which allowed American artillery to command the city of Boston, forced the evacuation of Boston before Howe was ready to move to the Hudson River. Believing he had nowhere near enough troops to conduct a successful offensive in New York, Howe instead moved his army to Halifax, Nova Scotia. Because of Benedict Arnold's invasion of Quebec, Howe's plans were further delayed as troops and artillery were required there. He was not at full strength until June when he finally decided to move against Staten Island.

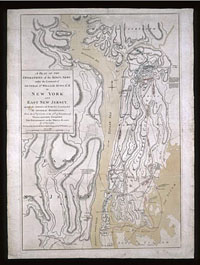

In the meantime, Washington sent Major General Charles Lee, a former British officer, to New York to prepare its defenses against just such an operation. Lee quickly reached the conclusion that a city surrounded by water was impossible to properly defend because of the power of the British navy and the inability of the Americans to do anything to stop it. "Whomever commands the sea must command the town," he wrote. Nevertheless, Lee came up with a plan that called for a series of fortifications at key points. To prevent British troops from landing on the East River that connects the Upper Bay of New York to Long Island Sound, Lee proposed a defensive post on Brooklyn Heights, which commanded the city. He also believed that King's Bridge, which connected Manhattan with the mainland, should be defended to prevent the British from cutting off the primary avenue of American escape from the city. Lee did not believe that his defenses would actually hold New York, but he did think that "it might cost the enemy many thousands of men to get possession of it." Washington arrived in New York in April 1776 and moved forward with Lee's plans for fortification (by then Congress had sent Lee to Charleston, South Carolina). He brought with him an army of almost 20,000 men, although the vast majority of them were infantrymen — Washington had few cannon, no cavalry, and not a single naval warship. Moreover, his troops were mainly militiamen and untrained recruits with a motley collection of weapons and wholly inexperienced officers to lead them. Washington's force was essentially an army of poorly equipped amateurs.

Howe landed on Staten Island unopposed on July 2, 1776, with more than 9,000 well-armed, highly trained, professional soldiers and 130 ships. More troops and 150 ships under his brother, Vice-Admiral Lord Richard Howe, joined him on July 12. Over the next several weeks thousands more British, Hessian, and other reinforcements reached Staten Island — and were warmly welcomed by the inhabitants. By August 12, Howe, who had been reinforced by Sir Henry Clinton's southern army, commanded an army of more than 31,000 men and a fleet of 10 ships-of-the-line, 20 frigates, hundreds of other vessels, and 10,000 sailors. Washington responded by dividing his forces among positions on Brooklyn Heights, Governor's Island, King's Bridge, Long Island, and at a crude earthwork structure named Fort Washington built on the Hudson River at what is now called Washington Heights.

Howe began his offensive on August 27 by surprising the Americans with a ferocious attack that enveloped their exposed left flank on Long Island. The Continental line collapsed and the troops ran from the field, turning the Battle of Long Island a British route. The victory was far from complete, however, because Howe did not pursue the shattered American force, which allowed Washington to masterfully manage the evacuation of the troops to Manhattan under the cover of darkness on the night of August 29. It was followed by a peace conference on Staten Island on September 11 between Benjamin Franklin, John Adams, and Edward Rutledge, representing Congress, and Admiral Howe, who had authority from British prime minister Lord North to negotiate with the erstwhile colonials. Because Howe did not have permission to broker any agreement that allowed for American independence, declared just a few months earlier, the conference was practically over before it began.

Faced with a dwindling army because thousands of militiamen were going home, Washington considered leaving New York to the British, but he believed that Congress wanted it held, so he decided to defend the city despite his problematic situation. After reorganizing his army into three "grand divisions," he made a major tactical mistake by spreading out his troops over 16 miles from the city through Harlem Heights and Kings Bridge to the East River. Congress informed him on September 14 that the decision to evacuate the city was his to make. Howe did not give him the opportunity to ponder the question for very long. On September 15, British warships sailed past American artillery batteries on the Hudson River and anchored off the city. At the same time, Howe landed 4,000 British and Hessian troops at Kips Bay on Manhattan Island and attacked the small force of Connecticut militia positioned there. The Americans fled, despite Washington's passionate attempts to rally them, and the entire line along the East River collapsed, leaving New York City wide open to Howe's troops. The British commander, however, failed to press his advantage to cut off the escape of American troops in the city. His delay gave Washington the chance to again elude catastrophe by evacuating his army to a strong defensive position on Harlem Heights. The British took control of the city and the next day a small advance force was repelled in a set of skirmishes in front of Washington's lines on the Heights. Howe attempted no other operations for the next several weeks, a period during which a large portion of the city — almost 500 buildings — was destroyed by a mysterious fire (on September 20 and 21).

Howe spent much of the next month laying the groundwork for a stratagem to surround Washington's forces. On October 12 he put his plan into action and within a week had compelled Washington to retreat from Harlem Heights, a move that cut Fort Washington off from the rest of the Continental Army. Howe attacked Washington's new position at White Plains on October 28 with 13,000 men. The British and Hessian soldiers drove the Americans from the hill that commanded the field and anchored Washington's right flank, which forced Washington to retreat yet again, this time farther to the northwest, to North Castle. Howe did not pursue the Continentals — even though he was in a position to deliver a fatal blow - but instead turned his attention to the two isolated forts that were now behind his lines. Fort Washington fell on November 16, along with its garrison of 3,000 soldiers and a substantial quantity of supplies. Howe captured Fort Lee, built on the New Jersey side of the Hudson River opposite Fort Washington, four days later. Most of its troops evacuated but they left behind yet another major cache of supplies, including 1,000 barrels of flour and 50 cannon.

The capture of the two forts effectively ended Howe's New York campaign as action shifted into New Jersey. Howe succeeded in taking New York City (which remained in British hands until December 1783), inflicted numerous casualties on Washington's army (including taking more than 4,000 prisoners), captured valuable materiel, and assumed control of the lower Hudson River. However, he failed to destroy the Continental Army, despite numerous chances to do so.