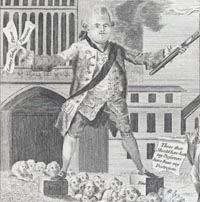

Frederick North, 2nd Earl of Guilford (1732-1792)

Frederick North, commonly known as Lord North, was British first or prime minister for almost the entirety of the American Revolution. He was born April 13, 1732, in London to Francis North, Baron (later Earl) Guilford, and his wife Lady Lucy Montagu, the daughter of the Earl of Halifax. After the death of North's mother in 1734, his father married Elizabeth Legge, whose son, William, the future Earl of Dartmouth, became North's close friend and political ally. North was educated at Eton and Trinity College, Oxford, and then went on a grand tour of Europe with Dartmouth that lasted three years, until 1754. Upon returning to England, North married 16-year-old Anne Speke, the daughter of a modest property owner in Somerset.

With a wealth of political connections (his uncle, Halifax, was President of the Board of Trade and his stepbrother's uncle was Chancellor of the Exchequer), North easily entered Parliament in 1754 representing the pocket borough of Banbury, a seat he held until 1790 when he advanced to the House of Lords as the Earl of Guilford. His most important early political post came with his appointment in 1759 as a Lord of the Treasury. He spent six years there, learning the intricacies of imperial finance. North remained in the government during the shifting administrations of the 1760s, but came into his own as a speaker in Parliament during the ministry of George Grenville, when he gained a well-deserved reputation for eloquence and perspicacity in representing the ministry's side against John Wilkes and in favor of passing the Stamp Act. North went into opposition when Grenville's ministry fell in 1766, but returned to the government as Chancellor of the Exchequer in the Chatham ministry after the death of Charles Townshend in September 1767. Already a member of the Privy Council (since 1766), North was an increasingly influential member in the Cabinet, especially after the Duke of Grafton succeeded Chatham as First Minister. He also became the ministry's leader in the House of Commons, once again in battle against John Wilkes (this time to expel him from Parliament). North's steadfast support for the government in Parliament and reliable counsel in the Cabinet earned for him the trust and esteem of George III, which did not waver until the end of the American War for Independence.

When Grafton ministry fell in January 1770, the King enthusiastically offered North the office of First Lord of the Treasury and the role of prime minister (a term North hated and forbade to be used around him). Only 37 years old, he accepted on January 28, 1770, and secured his position by winning several major votes over the next two weeks. North would remain in the office, leading from the floor of the House of Commons, for the next 12 years. One of his first acts was a successful motion to repeal almost all of the Townshend duties (except that on tea). He also succeeded in bringing the East India Company, which ruled over vast territories of the subcontinent, under some measure of imperial control by taking advantage of the company's financial weakness: In exchange for a massive loan and a duty-free monopoly on selling tea in the American colonies, the company was forced to accept substantial reform and oversight, if not yet outright control, from London. The only problem was that the plan to sell tea in America-the Tea Act of 1773-brought an end to the relative peace that characterized transatlantic relations since the repeal of the Townshend duties. The result was the Boston Tea Party on December 16, 1773.

When North first learned of the destruction of the tea in Boston Harbor, he favored a firm response but was reluctant to turn the matter over to Parliament, where he feared it would become a matter of constitutional principle rather than a question of enforcing the law. Upon learning that the crown did not have the constitutional authority to close the port of Boston until the tea was paid for, or the wherewithal to arrest unidentified leaders, North had little choice but to go to the House of Commons. The subsequent adoption of the Coercive Acts, all of which passed with overwhelming majorities, drove the colonies first into union and then into open rebellion against Great Britain. North quickly became the most hated man in America. In July 1774, Arthur Lee called him and his stepbrother, Dartmouth, "as perfect villains as any of the Age," who were "ready to execute the most diabolical measures." On November 3, 1774, a visitor to Virginia recorded in his journal that, "The Effigy of Lord North was shot at" in Alexandria, "then carried in great parade through the town and burnt."

North was open to conciliatory measures to avoid a total break with America. In February 1775, he declared on the floor of the Commons that he "did not mean to tax America." As far as he was concerned, if the colonies "would submit, and leave to us the constitutional right of supremacy, the quarrel would be at an end." Two weeks later he proposed that Parliament would eschew any taxation of the colonies if they agreed to pay for their governments, their courts, their defense, and assist the empire with men and money if it went to war, a proposal that appeared to have conceded the principle of "no taxation without representation." The Virginia House of Burgesses spoke for many when it opined, "It is not merely the mode of raising, but the freedom of granting our money for which we have contended."

The opportunity for any serious consideration of conciliation virtually evaporated after the Second Continental Congress moved forward with preparations for war in the aftermath of the Battles of Lexington and Concord in April 1775. George Germain, the Secretary of State for the Colonies, thereafter assumed primary responsibility for conducting the conflict, leaving North to pick up the pieces in Parliament after Burgoyne's surrender at Saratoga in October 1777. A peace commission was created in February 1778, the Tea Act and Massachusetts Government Act were repealed, and Parliament formally renounced its authority to tax the colonies. By then the Americans had joined in alliance with France and would accept no terms short of the recognition of independence. North himself saw little point in continuing the conflict, but George III would no sooner accept such an outcome than he would North's several attempts to resign. News of Cornwallis' surrender at Yorktown, however, put both matters beyond the King's power to influence, as it convinced a majority of members of Parliament that continuing the war was pointless. The King was forced to accept North's resignation when the opposition in the Commons won a motion on February 27, 1782, to end offensive operations in America.

Despite George III's intense feeling that North had deserted him by resigning, the former prime minister returned to office briefly in perhaps the most unlikely coalition Britain had ever seen: North joined Charles James Fox as Secretaries of State in a government nominally headed by the Duke of Portland. Coming into office in February 1783, the ministry did not live to see the end of the year, succeeded by a government headed by William Pitt ("the younger"). North entered the House of Lords in 1790 when his father died and the title of Earl of Guilford, along with its considerable wealth, descended to him. He did not have long to enjoy either as he died in London on August 5, 1792.